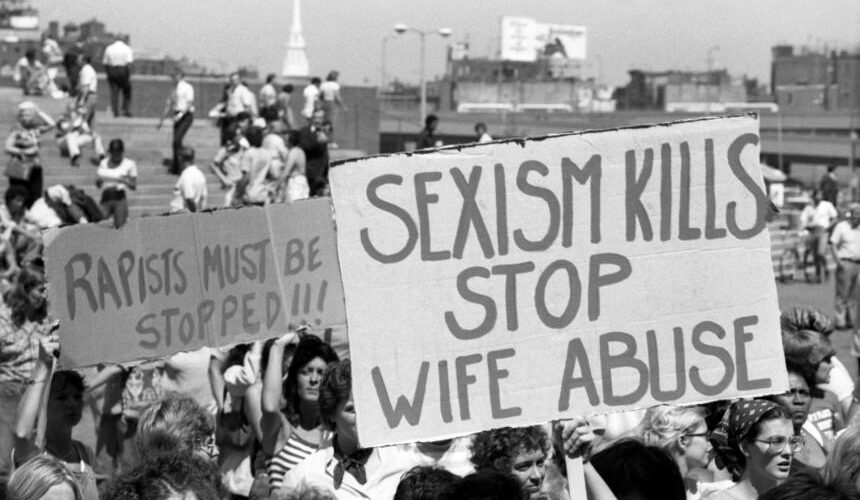

This chapter rejects both traditional sexual repression and uncritical models of sexual “liberation.” This idea disrupts the assumption that sexuality should conform to male-centered standards of dominance, availability, and compulsory heterosexuality. This shift in ideology threatens social stability because it questions long-standing beliefs that women’s bodies exist for male access, that sexual activity is a social obligation, and that heterosexuality is the natural/superior norm. hooks shows that confronting sexual oppression also exposes divisions within feminism itself, particularly when rigid ideas about “politically correct” sexuality alienate large numbers of women. Ultimately, the movement’s power lies in its insistence on redefining sexuality as a site of choice, autonomy, and mutual respect, rather than coercion—an approach that challenges cultural, institutional, and interpersonal systems built on sexual control and inequality.

Author: Annie Hall

bell hook’s “Feminist Movement to End Violence” (1984)

1946-1989, Black, Date, Defining the Enemy, Patriarchy, Subjectives of Refusal, White Supremacy, WomenThis chapter in bell hooks’ book “Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center” challenges deeply normalized beliefs about power, authority, and violence in everyday life. Instead of merely condemning individual acts of male violence against women, she describes a movement that disrupts social norms by exposing how violence is embedded in hierarchical systems such as patriarchy, capitalism, white supremacy, and the family itself. This perspective unsettles societal norms because it forces both men and women to confront their own participation in and acceptance of coercive power, including the ways violence is justified as discipline, love, protection, or authority. By questioning long-standing assumptions that domination is natural and necessary, this movement threatens institutions that rely on control and obedience. hooks argues that this disruption is necessary, because ending violence requires transforming cultural values and social relationships at their core, not merely managing or punishing violent behavior after it occurs.

Jane M. Jacobs’ “Earth and Honoring: Western Desires Indigenous Knowledges” (1994)

1990-2010, Date, Defining the Enemy, Imperialism, White SupremacyWestern engagement with Indigenous knowledge often disrupts the existing structures within Indigenous communities. By framing Indigenous knowledge as objects of desire for environmental or feminist agendas, Western actors inadvertently impose external norms on communities with their own political and cultural priorities. This can disrupt traditional authority structures, gender roles, and decision-making practices, as Indigenous knowledge is selectively highlighted to fit Western narratives. This text shows that even well-intentioned alliances may reproduce colonial power dynamics, privileging Western perspectives while undermining Indigenous agency. The objectification of Indigenous knowledge by the West has created tension between maintaining cultural sovereignty and engaging with broader political movements.

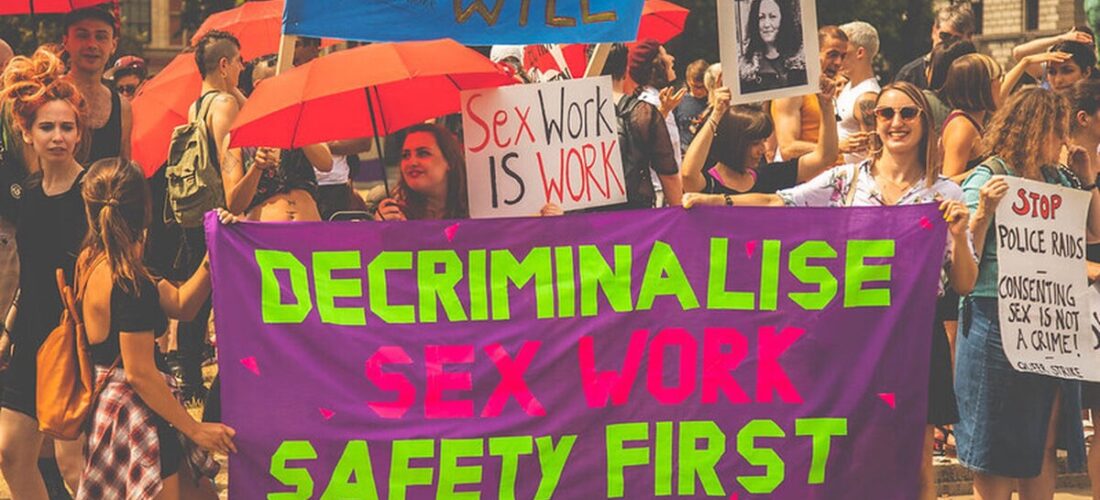

Alison Murray’s “Debt-Bondage and Trafficking: Don’t Believe the Hype” (1998)

1990-2010, Date, Defining the Enemy, Imperialism, Subjectives of Refusal, Women, WorkersMurray describes how sex workers challenged dominant feminist, governmental, and media narratives about trafficking and exploitation. The anti-trafficking campaigns of the 1990s shifted public discourse by framing prostitution almost exclusively through sensationalized stories of slavery, coercion, and victimhood, but this assertion was countered by sex workers’ own political organizing, especially at the 1995 Beijing UN Conference. By asserting their agency, contesting inflated statistics, and demanding recognition of sex work as labor, sex workers unsettled abolitionist feminism and exposed how moral panic, racism, and restrictive immigration laws intensified exploitation rather than alleviating it. This conflict fractured feminist alliances, weakened the credibility of abolitionist campaigns, and forced international institutions to confront the limits of universal claims about women’s oppression, reshaping debates on migration, labor, and women’s rights in a globalized economy.

“Blanket statements about prostitution and the exploitation of women are propaganda from a

political agenda which seeks to control the way people think and behave.”

Hazel V. Carby’s “On the Threshold of Woman’s Era” (1985)

1946-1989, Black, Date, Defining the Enemy, Patriarchy, Subjectives of Refusal, White Supremacy, WomenCarby writes about how Black feminist thought emerged in direct opposition to the racial, sexual, and imperial systems that structured American society. She discusses how lynching functioned not only as racial terror against Black men but also as a means of regulating Black women’s sexuality and silencing their political agency, reinforcing white supremacy and patriarchal power. Black women’s activism disrupted this order by challenging dominant narratives that portrayed white women as the sole victims of sexual violence while erasing the experiences of Black women. By organizing against lynching, imperialism, and racist representations of sexuality, Black women exposed the limits of mainstream feminism and destabilized its universal claims about womanhood. This resistance forced a redefinition of feminist politics, showing how struggles against racism reshaped existing ideas of gender, power, and social order.

Natalie Zemon Davis’ “Iroquois Women, European Women” (1973)

UncategorizedDavis shows that Indigenous women resisted traditional European gender roles by maintaining forms of authority and autonomy that sharply contrasted with French patriarchal norms. European observers expected women to be submissive, economically dependent, and excluded from decision-making, yet Iroquois women controlled agriculture, household resources, and kinship through matrilineal and matrilocal systems. Senior women exercised influence within the longhouse, could initiate divorce, retained custody of children, and had decisive power over daily economic life—practices that undermined European assumptions about male dominance within the family. Even when exposed to Christianity, some Indigenous women adapted the new religion to expand their public voice, preaching, teaching, and leading prayer despite missionaries’ insistence on female obedience. Rather than passively accepting European gender ideals, Iroquois women reshaped colonial encounters to preserve their authority.

“If a man wanted a courteous excuse not to do something he could say without fear of embarrassment ‘that his wife did not wish it.’”

Chandra Talpade Mohanty’s “Under Western Eyes” (1984)

1946-1989, Date, Defining the Enemy, ImperialismMohanty explains in her essay how Western feminist scholarship applies universal categories of gender and oppression to women in the Global South. She argues that this disrupts the true meaning of feminism because the diverse histories and lived experiences of non-Western women are flattened into the singular figure of the “Third World woman,” erasing cultural, class, and political differences. Such discursive homogenization distorts feminist political practice by reinforcing hierarchical power relations between Western and non-Western women and undermining the possibility of meaningful transnational solidarity. By positioning Western women as the norm, colonial legacies within feminist discourse itself are reproduced, disrupting efforts to build coalitions grounded in shared but context-specific struggles. Mohanty frames this disruption not as a breakdown of feminism, but as a critical failure that demands more historically situated, self-reflexive feminist analysis.

“It is in the production of this ‘third-world difference’ that western feminisms appropriate and colonize the constitutive complexities which characterize the lives of women in these countries.”

Aihwa Ong’s “State Versus Islam: Malay Families, Women’s Bodies and the Body Politic in Malaysia” (1987)

1946-1989, Date, Subjectives of Refusal, WomenOng describes the emerging disruption from the growing tension between Islamic revivalism and the Malaysian state’s modernization project in this essay. This disruption is the most clear in daily family life and in the regulation of women’s bodies, where new moral expectations challenge the previously flexible Malay social practices. As Islamic movements seek to impose stricter codes of dress, sexuality, and gender behavior, women become symbolic sites through which broader concerns around national identity, modernity, and religious authority are negotiated. The resulting disruption does not produce social collapse, but a reorganization of power, as both the state and Islamic institutions extend their control over intimate aspects of life. Ong frames this social disruption as a contested process that reshapes norms, identities, and governance in Malaysia, revealing how gender becomes central to managing social change.

Angela Davis’ “Racism, Birth Control and Reproductive Rights” (1981)

1946-1989, Black, Date, Defining the Enemy, Patriarchy, Subjectives of Refusal, White Supremacy, WomenAngela Davis explains in her essay how the history of reproductive control over Black women reveals the limitations of liberal and feminist frameworks. Davis presents birth control as a subject entangled with racism, eugenics, and population control, particularly in relation to poor and Black communities. She shows how institutions that claimed to advance women’s freedom, such as public health systems, welfare policies, and mainstream feminist movements, simultaneously relied on the regulation of Black women’s reproduction while denying them reproductive autonomy. Black women emerge as a disruptive figure within these systems, as their lived experiences challenge the assumption that reproductive rights are universally emancipatory. By centering practices of coerced sterilization and racially targeted population control, Davis disrupts dominant narratives of progress and individual choice, exposing the contradictions and exclusions that structure prevailing social and political conceptions of reproductive freedom.

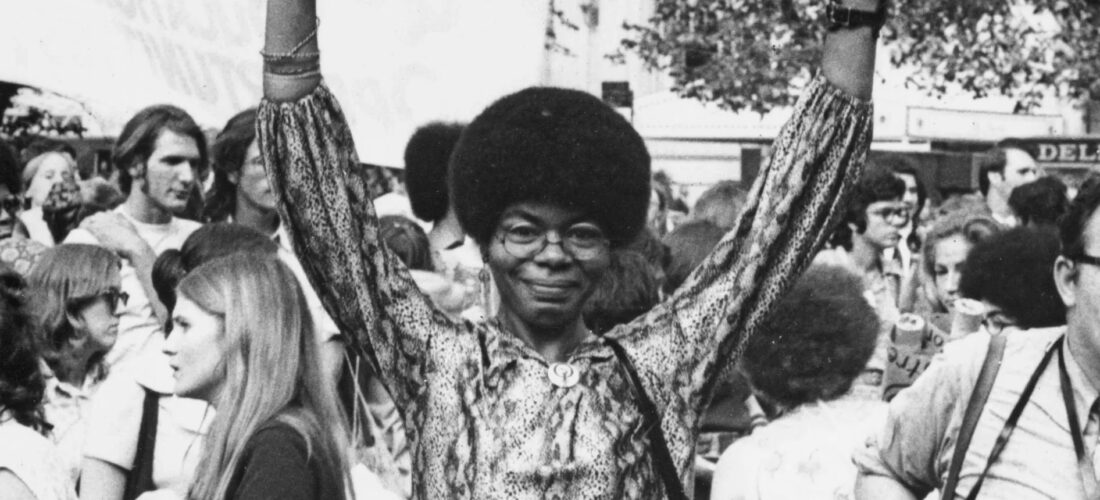

Audre Lorde’s “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” (1979)

1946-1989, Black, Date, Defining the Enemy, Patriarchy, Queer, Subjectives of Refusal, White Supremacy, WomenAudre Lorde challenges dominant White feminist frameworks by insisting that race, class, and sexuality are essential intersectional perspectives for disrupting enduring patriarchal structures. The American feminist agenda has historically dismissed the voices of marginalized women, and these exclusions erase any possibility of genuine collective struggle. Lorde critiques the contradiction of analyzing a racist patriarchy through the very tools produced by that same racist patriarchy, highlighting how such approaches only reinforce existing power relations. To counter this, she calls for the active participation and leadership of lesbian women and Third World women, whose experiences and perspectives offer the foundations necessary for building a form of feminism that is truly transformative.

“I urge each one of us here to reach down into that deep place of knowledge inside herself and touch that terror and loathing of any difference that lives there. See whose face it wears. Then the personal as the political can begin to illuminate all our choices.”

Fadwa El Guindi’s “Veiling Resistance” (1999)

1990-2010, Colonized, Date, Subjectives of Refusal, WomenEl Guindi argues that contemporary veiling is not simply a result of patriarchal structures, but a conscious rejection of Western ideologies and colonial legacies. Historically, veiling has signified honor, status, and social identity, resisting Western narratives that depict the practice as strictly oppressive. Western thinkers have distorted Islamic understandings of gender, often portraying Islamic societies as culturally inferior. For many women, veiling becomes a way to negotiate privacy and create an identity that is religious, cultural, and modern. Muslim women activists who have advocated for women’s rights from within Islamic frameworks further challenge the Western assumption that Islam is inherently antifeminist and undermine universalizing Western feminist conceptions of “women’s rights.” This essay disrupts existing Western perceptions of Islamic culture and gender norms.

Ania Loomba’s “Dead Women Tell No Tales”

1990-2010, Colonized, Date, Defining the Enemy, Imperialism, Patriarchy, Subjectives of Refusal, WomenLoomba’s essay traces how the sati-widow has been represented from the colonial period through postcolonial debates. Sati is a historical Hindu practice in which a widow is burned alive on her deceased husband’s funeral pyre, either voluntarily or by coercion. Loomba explains how the very societal systems that have attempted to define her—colonial, patriarchal, nationalist, and feminist—are disrupted by the sati-widow figure. Each of these systems relied on the widow as a symbolic figure, but simultaneously erased her subjectivity. This erasure forces a rethinking of these prevailing narratives, proving the instability of the social, cultural, and epistemic frameworks that sought to confine her.

The Zapatista Women’s Revolutionary Law (1994)

1990-2010, Date, Defining the Enemy, Indigenous, Patriarchy, Subjectives of Refusal, WomenThe Zapatista Women’s Revolutionary Law establishes women’s rights within the context of the Zapatista armed indigenous uprising. It guarantees women the right to participate in the revolutionary struggle, access work with equal pay, exercise reproductive autonomy, participate in community decision-making, and receive equal social rights. The law frames women’s liberation as inseparable from broader social and indigenous resistance, linking gender equality directly to the fight against oppression.

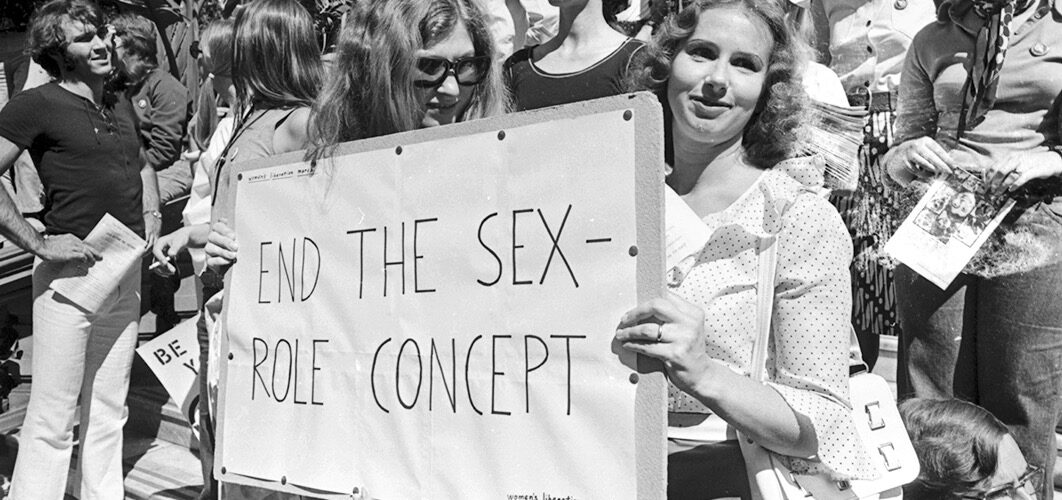

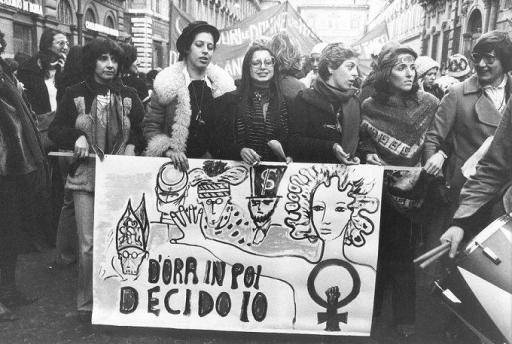

Manifesto of Female Revolt (Rivolta Femminile) (1970)

1946-1989, Defining the Enemy, Patriarchy, Subjectives of Refusal, WomenThe Manifesto of Rivolta Femminile disrupted societal norms in Italy by openly rejecting the foundations of the country’s patriarchal social order during a time when rigid gender roles remained largely unquestioned. It describes marriage, motherhood, and women’s unpaid domestic labor as instruments used to suppress women. The manifesto challenges not only the domestic sphere but also the moral authority of the Church and the political agenda of the male-dominated Left, including Marxist ideals, and it calls for the dismantling of established political movements that had previously expected feminist demands to be absorbed into broader class-based struggles.

“Liberation for woman does not mean accepting the life man leads, because it is unlivable; on the contrary, it means expressing her own sense of existence.”

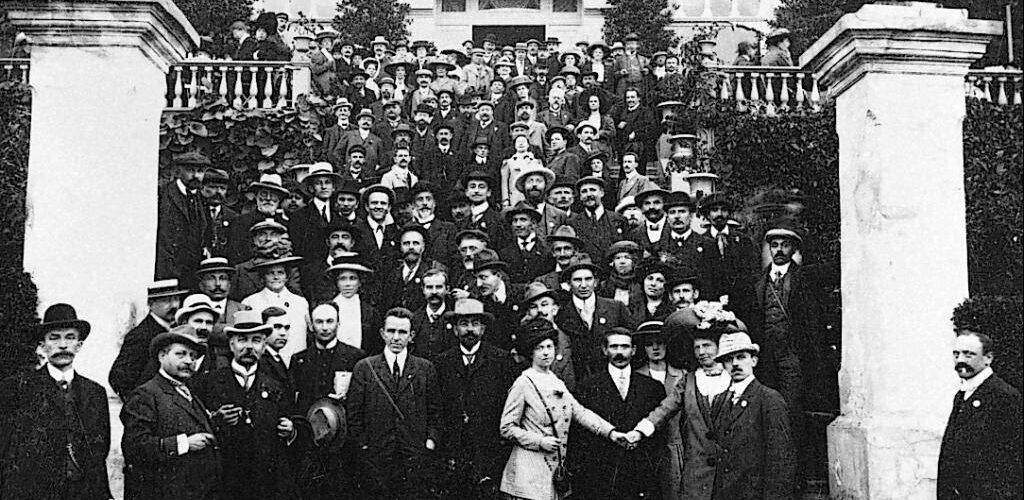

First International Conference of Socialist Women (1907) and Second International Conference of Socialist Women (1910)

1840-1945, Defining the Enemy, Patriarchy, Subjectives of Refusal, The Bourgeoisie, Women, WorkersThe First (1907) and Second (1910) International Conferences of Socialist Women manifestos directly challenged the political, economic, and gender structures that existed during these times. Instead of seeking incremental reforms or aligning with the ideals of mainstream middle-class feminism, they redefine women’s liberation as inseparable from a working-class revolution. They reject “bourgeois” feminist agendas that ignored the material realities of laboring women. They demanded universal suffrage as a tool of class struggle, declared capitalism to be the root of women’s exploitation, and insisted that women enter unions, strikes, and political organizations. These manifestos disrupted both traditional gender norms and the preexisting economic order. Their creation of international coordination further unsettles national boundaries and portrays women as a global political force. Through asserting that true emancipation requires fundamental restructuring of society, not mere reform, these documents articulate a bold and disruptive display of feminist politics that threatened the stability of existing power systems.

Hawon Jung’s Flowers of Fire (2023)

2011-Present, Defining the Enemy, Patriarchy, Subjectives of Refusal, WomenHawon Jung draws attention to the personal testimonies and protests that have unfolded in South Korea as a result of persistent gender-based violence. She shows how women’s collective voices have shattered long-standing norms of silence and obedience deeply rooted in the country’s entrenched patriarchy. This activism has challenged not only individuals but also the institutions that have historically protected male authority. The women who participate in this resistance disrupt generational continuity, redefining womanhood in ways that no longer revolve solely around family life and men.

“Wake up! Your Miss Saigon was dead and gone a long time ago. She’s not here anymore.”

Resistance Through No Sex: The 4B Movement in South Korea

2011-Present, Defining the Enemy, Patriarchy, Subjectives of Refusal, Uncategorized, WomenWomen in South Korea have continuously been treated as inferior under a deeply ingrained patriarchal system. In 2016, after a young woman was murdered in a misogynistic hate crime, the country reacted with outrage over the poor handling of her case. Misogynistic crimes like this, combined with systemic gender inequality and intense societal pressures, helped spark a collective rejection of men and patriarchal norms. Although often described as a “sex strike,” that is not the sole purpose of the 4B movement. Women in South Korea also place greater emphasis on engaging with and supporting one another rather than conforming to traditional relationships with men.

”The 4B thing is a very Korean, feministic lifestyle, and it is irreversible. We cannot be taken back again!”

Life Without Men: The 4B Movement

2011-Present, Defining the Enemy, Patriarchy, Subjectives of Refusal, Uncategorized, WomenAfter a history of oppression, rigid gender roles, pervasive misogyny, and gendered violence, many South Korean women have collectively decided to reject traditional patriarchal structures. These women follow the principles of the “4Bs”: bihon (no marriage), bichulsan (no childbirth), biyeonae (no dating men), and bisekseu (no sex with men). Through these rejections, they are not only resisting gender discrimination but also destabilizing societal expectations—with no clear desire to return to traditional roles, even in the aftermath of mass protests. This social disruption has begun to expand westward, reaching beyond Korea’s borders.

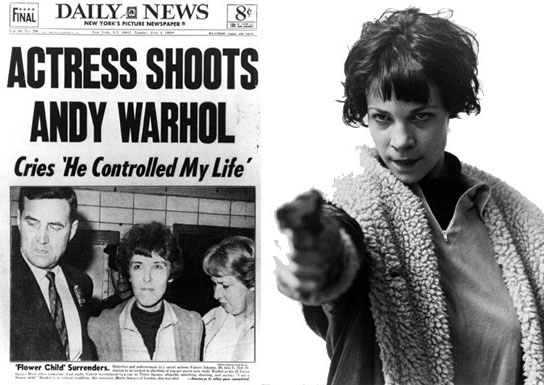

Valerie Solanas’s S.C.U.M. Manifesto (1967)

1946-1989, Date, Defining the Enemy, Patriarchy, Subjectives of Refusal, WomenThe S.C.U.M. Manifesto is an account of Valerie Solanas’s radical feminist views. She argues that men are incomplete women who spend their lives attempting to become female. Through this pursuit, men have corrupted the world by forming harmful systems that give them a false sense of purpose. To relieve society of this corruption, women must recognize the damage caused by men and tear apart the systems that are ruining the nation. Ultimately, Solanas advocates the eradication of men.

“To be male is to be deficient, emotionally limited; maleness is a deficiency disease and males are emotional cripples.”